You might be aware of the fact that Preston is home to an infamous and controversial building… the bus station!

This infamous building is often described as being like Marmite- you either love it or loathe it! But why is it so divisive? Let us try to find out…

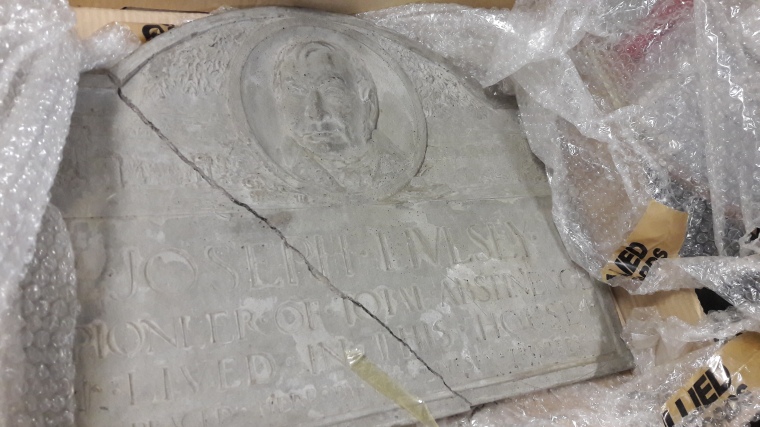

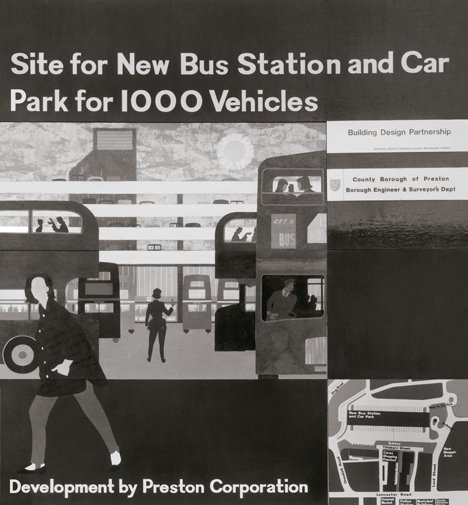

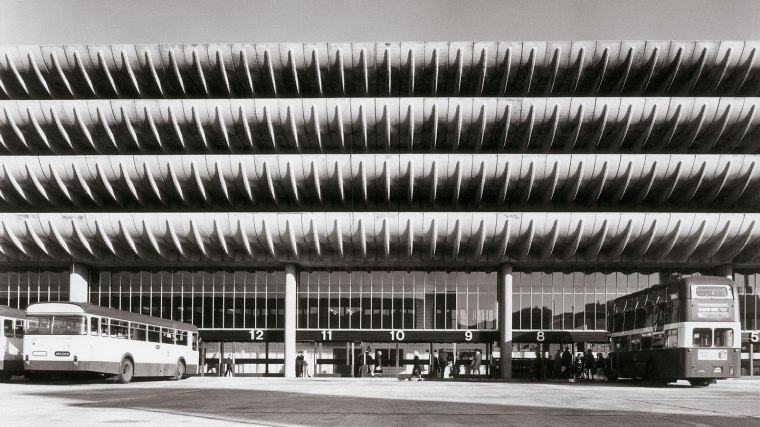

It was designed by Keith Ingham and Charles Wilson, who belonged to the Building Design Partnership, a firm of architects and engineers that was founded by the Prestonian architect George Grenfell Baines. They worked together with engineers from Ove Arup and Partners, and building work began in 1968, being completed in 1969. It was designed to accommodate 80 double decker buses and 1,100 cars, and it is still one of the largest bus stations in the world.

Side note: Nick Park, the creator of Wallace & Gromit and UCLan SU meeting room namesake, has a connection to the Preston bus station, as his father worked as a photographer for the Building Design Partnership. Check out our blog about him here!

But why does it stir up so many passions? Why is it often called ‘ugly’?

The building was built in a style called ‘Brutalism’, which was a modernist architectural movement that took its name from the French word for “raw”. This in turn came from the favoured building material choice of many architects of béton brut, raw concrete. It was popular from the 1950s until 1970s, and it became popular with governmental projects. Examples are found worldwide, and they are easily identified with their fortess-like appearance and the predominant use of exposed concrete construction, which can seem forbidding. The concrete would often expose the construction work, and was often designed to have a certain sculptural quality to it.

The rugged, not easily accessible look of the designed buildings could be interpreted as a reaction of younger designers to the smooth, light designs of the Art Deco era. This can be found in the design of the Preston Bus Station, where the car park balconies incorporate distinctive curves in exposed raw concrete. These balconies are the most recognisable feature of the structure, and they are functional, as they protect car bumpers from crashing against a vertical wall. It was also meant to have a sculptural quality to it.

It is noteworthy that many original features are still in place- the bold Helvetica signage and big Swiss railway-style clocks. The quality of the materials used is also noteworthy: bespoke handrails and the white tiles on the exterior and interior, produced by Shaws of Darwen, the same kind used in Harrods. It can be argued that such a standard of finish in public buildings would be unusual today, and whilst the appearance of these features might look rundown today, one must keep in mind that materials age in every building, be it Victorian or Brutalist, and the upkeep of a structure contributes to its appearance.

It was Grade II listed in 2013, which means that the building is of special architectural interest and warrants every effort to preserve it, after it was threatened with demolition. At the moment of writing it is undergoing extensive refurbishment, and it will probably be completed by 2019. The scheme is designed to revitalise the area, and a building accommodating a youth zone will be built next to it. Hate it or love it, it is doubtlessly one of Preston’s most famous building, and it will doubtlessly continue to cause divisions.

On a side note, many Victorian buildings were once deemed as ‘ugly’, but attitudes changed over time. The famous St Pancras Station in London for example was threatened with demolition in the 1960s, and only a campaign saved the building from this fate. Maybe the attitudes towards the Preston Bus Station will change over time towards a more favourable picture.

Picture credits

Preston Bus Station, image via http://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=495159

Preston Bus Station, image via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preston_bus_station#/media/File:Preston_bus_station_232-26.jpg

Preston Bus Station Development by Preston Corporation, image via https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/12/brutalist-buildings-preston-bus-station-by-building-design-partnership/

Preston Bus Station Interior, Image via https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/12/brutalist-buildings-preston-bus-station-by-building-design-partnership/

Roger Park, Preston Bus Station, image via http://www.bdp.com/en/projects/p-z/Preston-Bus-Station